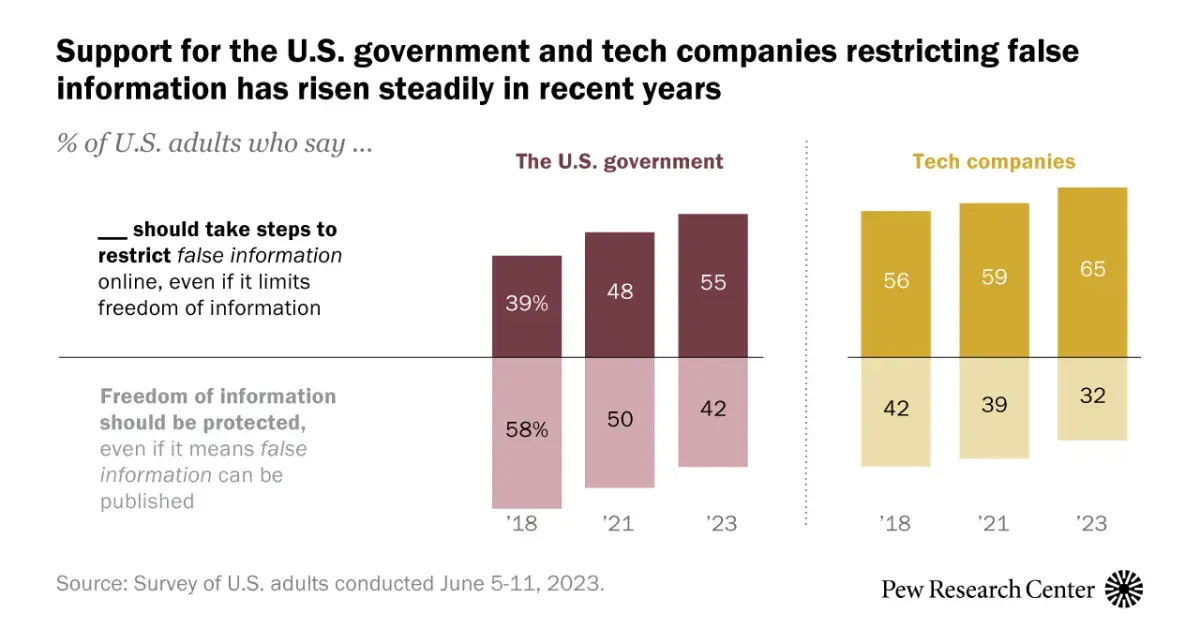

65% of Americans support tech companies moderating false information online and 55% support the U.S. government taking these steps. These shares have increased since 2018. Americans are even more supportive of tech companies (71%) and the U.S. government (60%) restricting extremely violent content online.

Most Americans agree that false information should be moderated, but they disagree wildly on what’s false or not.

I personally like transparent enforcement of false information moderation. What I mean by that is something similar to beehaw where you have public mod logs. A quick check is enough to get a vibe of what is being filtered, and in Beehaw’s case they’re doing an amazing job.

Mod logs also allow for a clear record of what happened, useful in case a person does not agree with the action a moderator took.

In that case it doesn’t really matter if the moderators work directly for big tech, misuse would be very clearly visible and discontent people could raise awareness or just leave the platform.

Y’all gonna regret this when Ron DeSantis gets put in charge of deciding which information is false enough to be deleted.

What a slippery slippery slope….

65% of Americans support tech companies moderating false information online

aren’t those tech companies the one who kept boosting false information on the first place to get ad revenue? FB did it, YouTube did it, Twitter did it, Google did it.

How about breaking them up into smaller companies first?

I thought the labels on potential COVID or election disinformation were pretty good, until companies stopped doing so.

Why not do that again? Those who are gonna claim that it’s censorship, will always do so. But, what’s needed to be done is to prevent those who are not well informed to fall into antivax / far-right rabbit hole.

Also, force content creators / websites to prominently show who are funding / paying them.

aren’t those tech companies the one who kept boosting false information on the first place to get ad revenue?

Not really, or at least not intentionally. They push content for engagement, and that’s engaging content. It works the same for vote based systems like Reddit and Lemmy too, people upvote ragebait and misinformation all the time. We like to blame “the algorithm” because as a mysterious evil black box, but it’s really just human nature.

I don’t see how breaking them up would stop misinformation, because no tech company (or government frankly) actually wants to be the one to decide what’s misinformation. Facebook and Google have actually lobbied for local governments to start regulating social media content, but nobody will touch it, because as soon as you start regulating content you’ll have everyone screaming about “muh free speech” immediately.

Do they agree on the definition of the false information?

If the FCC can regulate content on television, they can regulate content on the internet.

The only reason the FCC doesn’t is the Republican-dominated FCC when Ajit Pai was in charge argued that broadband is an “information service” and not a “telecommunications service” which is like the hair splittingest of splitting fucking hairs. It’s fucking both.

Anyway, once it was classified as “information service” it became something the FCC (claimed it) didn’t have authority to regulate in the same way, allowing them to gut net neutrality.

If they FCC changed the definition back to telecommunications, they wouldn’t be able to regulate foreign websites, but they can easily regulate US sites and regulate entities who want to do business in the US using an internet presence.

There are surely pros and cons, possibly good and possibly bad outcomes with such restrictions, and the whole matter is very complicated.

From my point of view part of the problem is the decline of education and of teaching rational and critical thinking. Science started when we realized and made clear that truth – at least scientific truth – is not about some “authority” (like Aristotle) saying that things are so-and-so, or a majority saying that things are so-and-so. Galilei said this very clearly:

But in the natural sciences, whose conclusions are true and necessary and have nothing to do with human will, one must take care not to place oneself in the defense of error; for here a thousand Demostheneses and a thousand Aristotles would be left in the lurch by every mediocre wit who happened to hit upon the truth for himself.

The problem is that today we’re relegating everything to “experts”, or more generally, we’re expecting someone else to apply critical thinking in our place. Of course this is unavoidable to some degree, but I think the situation could be much improved from this point of view.

The key is defining terms like “false” and “violent.”

But how do you implement such a thing without horrible side effects?

It’s all fun and games till well intentioned laws get abused by a new administration. Be careful what you wish for. My personal take is that any organization that is even reasonably similar to a news site must conform to fairness in reporting standards much like broadcast TV once had. If you don’t, but an argument could be made that you present as a new site, you just slap a sizeable banner on every page that you are an entertainment site. Drawing distinctions on what is news and what is entertainment would theoretically work better than an outright ban of misleading content.

At the end of the day it won’t matter what is written unless the regulations have actual teeth. “Fines” mean so little given the billion dollar backers could care less and retractions are too little too late. I want these wannabe Nazi “News Infotainment” people to go to jail for their speech that causes harm to people and the nation. Destroying democracy should be painful for the agitators.

Checks out. I wouldn’t want the US government doing it, but deplatforming bullshit is the correct approach. It takes more effort to reject a belief than to accept it and if the topic is unimportant to the person reading about it, then they’re more apt to fall victim to misinformation.

Although suspension of belief is possible (Hasson, Simmons, & Todorov, 2005; Schul, Mayo, & Burnstein, 2008), it seems to require a high degree of attention, considerable implausibility of the message, or high levels of distrust at the time the message is received. So, in most situations, the deck is stacked in favor of accepting information rather than rejecting it, provided there are no salient markers that call the speaker’s intention of cooperative conversation into question. Going beyond this default of acceptance requires additional motivation and cognitive resources: If the topic is not very important to you, or you have other things on your mind, misinformation will likely slip in.

Additionally, repeated exposure to a statement increases the likelihood that it will be accepted as true.

Repeated exposure to a statement is known to increase its acceptance as true (e.g., Begg, Anas, & Farinacci, 1992; Hasher, Goldstein, & Toppino, 1977). In a classic study of rumor transmission, Allport and Lepkin (1945) observed that the strongest predictor of belief in wartime rumors was simple repetition. Repetition effects may create a perceived social consensus even when no consensus exists. Festinger (1954) referred to social consensus as a “secondary reality test”: If many people believe a piece of information, there’s probably something to it. Because people are more frequently exposed to widely shared beliefs than to highly idiosyncratic ones, the familiarity of a belief is often a valid indicator of social consensus.

Even providing corrections next to misinformation leads to the misinformation spreading.

A common format for such campaigns is a “myth versus fact” approach that juxtaposes a given piece of false information with a pertinent fact. For example, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention offer patient handouts that counter an erroneous health-related belief (e.g., “The side effects of flu vaccination are worse than the flu”) with relevant facts (e.g., “Side effects of flu vaccination are rare and mild”). When recipients are tested immediately after reading such hand-outs, they correctly distinguish between myths and facts, and report behavioral intentions that are consistent with the information provided (e.g., an intention to get vaccinated). However, a short delay is sufficient to reverse this effect: After a mere 30 minutes, readers of the handouts identify more “myths” as “facts” than do people who never received a hand-out to begin with (Schwarz et al., 2007). Moreover, people’s behavioral intentions are consistent with this confusion: They report fewer vaccination intentions than people who were not exposed to the handout.

The ideal solution is to cut off the flow of misinformation and reinforce the facts instead.

Canadians: First time?

Your comment seems to imply it’s a bad thing. Do you have bad experiences with censorship?

In other news: most Americans disagree on what information is false